This week’s guest post is by Tracy Truels, Director of Learning and Engagement at Oklahoma City Museum of Art. Tracy has also worked at museums in Houston and New York. In addition to her work in museums, Tracy is a writer of fiction and operas.

The views expressed in this post are Tracy’s own, and do not represent the views of any particular museum.

When art museum directors are hired, the word “vision” shows up consistently in press releases announcing the news. Just in the last few years, examples abound. A search committee member from the Art Institute of Chicago described James Rondeau as the clear choice to fill the role of “an inspired leader whose vision and skill could match our bold aspirations.” Upon the hiring of Mathew Tietelbaum at MFA Boston, the chair of the board described the new director as having “a vision for how art can change lives.” At the Brooklyn Museum, director selection Anne Pasternak was described as “a true visionary [who] understands the power of art to transform communities.” Less than a year ago, Dr. Agustín Arteaga was announced as the next leader of the Dallas Museum of Art, and described as someone who will serve with “managerial acumen, curatorial expertise, and vision.”

I wish all of the above directors the best of success. But I wonder: How can someone have a vision for a place she hasn’t even worked at yet? If a director is too exact with his plans, is he really listening to museum staff?

The art museum world has become newly aware that museum directors need to have a good management track record, or at least to work with someone who does, as evident in high profile leadership changes at large institutions like the Dallas Museum of Art (DMA) and Metropolitan Museum of Art. It is not surprising in the least that the DMA nestled the phrase “managerial acumen” in their exaltations of Arteaga. Yet despite recognition that a museum director must be a strong manager, the formula here still seems to be the following:

- Find a really awesome person

- Give them all the power, which leads us to

- An Awesome Museum

It’s efficient, that’s for sure. The board only has to communicate with one person. That person then gets all the credit (or blame) for what happens. This strategy also meshes pretty perfectly with the classic organizational hierarchies still in place at most museums.

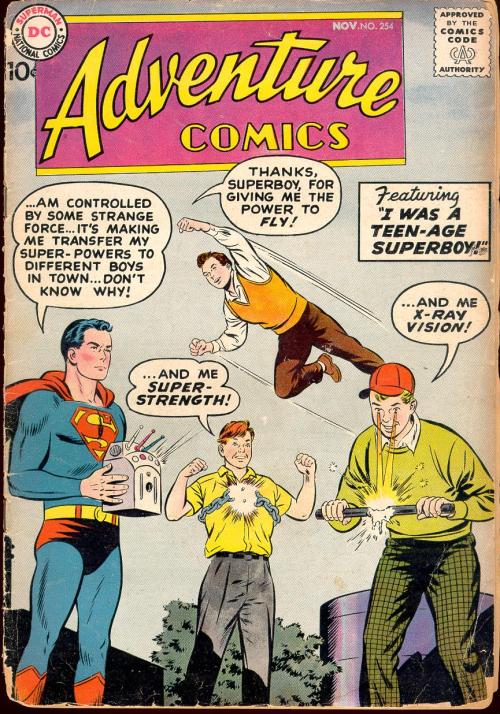

This thinking is not unique to museum culture, either. A principal comes in to “save” a failing school, a for-profit board brings in a CEO who will magically remake a failing business model. Basically, leaders are assigned the role of superheroes who live and work among us.

And the rest of the staff? Managers and front-line practitioners both function at best as efficient executors of “the vision.” In the ideal version of this scenario, a powerful director is loved by most if not all staff, who are happy to carry out this person’s vision. (Hold your breath, however, when that director leaves.) More often, there’s confusion and anxiety amongst staff members about how a new director’s plans will impact their work. Without a system where feedback from all levels is incorporated, the good ideas from staff simply die on the vine.

What is “Vision”?

A vision isn’t a series of catchphrases repeated at funder meetings, nor is it the result of one person’s personal career trajectory. A vision is an ideal your museum works to manifest inside the world we actually live in. It’s a reason for being.

In the past month, I have heard two directors, both of whom are interested in new models of museum leadership, reference Simon Sinek’s 2009 TED Talk “How Great Leaders Inspire Action.” Positing that organizations have to start with the “why,” Sinek states that “people don’t buy what you do; people buy why you do it.” He puts forward the idea that people will act when they’re inspired.

I once heard Beth Tuttle say that people can’t just like your museum, they need to love it. We have to compel our visitors to want to make the museum part of their precious free time. Shared vision allows staff and volunteers to carry the weight of that call together, to investigate what that ideal might look like so that our visitors want to be part of it, too.

The best CEOs and Museum Directors will welcome this transition from lone visionary to instigator of a shared vision, but it is not easy. Essentially, it requires executives to both own and be transparent about their authority, while simultaneously giving some of it away.

Shared Vision

How exactly might shared vision work? As with every other aspect of leadership, communication is vital. Executives must be open and candid with staff, including about why they took the job in the first place. It can begin with basics. Why did she begin working in museums in general? What inspires him about the field right now? What potential for this particular institution can be seen from an outside perspective? If the institution already has a stated vision, how is that vision evident in practice? Specifics are not only preferred but necessary, and make the difference between coming off as authentic rather than insincere.

With shared vision, communication is not one-way. Leaders need to ask their staff: Why do you come to work every day? What is this museum’s purpose? Can you share one particular moment in working here when you felt our museum’s purpose was truly being fulfilled? What is your dream for this place? What could be better about our organization? These questions are open-ended and require listening. Multiple opportunities should be given for staff to contribute, and not necessarily in public forums. Leaders have usually mastered the art of extroversion so preferred in executive culture, but that doesn’t mean it’s a requirement for everyone.

At some point the vision must be articulated, whether it be totally new or an evolution of what’s been before. Articulation of a vision is a director’s opportunity to inspire staff, to issue a call for people to answer in their museum work. Furthermore, this expression of vision gives everyone a common language. After all, how can we work to achieve a vision if we cannot say what it is?

Much of this endeavor takes place in the realms of organizational culture and management. Leaders must create an environment where vision is seen and talked about through the way we work and interact with one another.

Putting Shared Vision into Action: Rethinking Bureaucracy

When enacting a truly shared vision, how we carry something out becomes just as important what we are carrying out. In this way, we can take a cue from the artists we celebrate. To an artist, process and technique are a crucial part of the overall project. In many ways, the process is the thing itself. I’m talking about nerdy operations stuff now—meeting structures, feedback processes, thoughtful, ongoing evaluation, and modesty on the part of pretty much everyone.

For those museums working with traditional top-down organizational charts, this means tearing down some walls. This is hard.

A Harvard Business Review article from March 2016 states that “any bureaucracy-bound organization that wants to overhaul its management model will have to invent its own map.” The authors actually suggest staff hacks of the bureaucracy itself:

Imagine an online, company-wide conversation where superfluous and counter-productive management practices are discussed and alternatives proposed. The output of such a conversation wouldn’t be a single, elaborate plan for uprooting bureaucracy, but a portfolio of risk-bounded experiments designed to test the feasibility of post-bureaucratic management practices.

I don’t know if they’ve tried hacking their own bureaucracy, but the Minneapolis Institute of Art (Mia) has made demonstrable strides in the area of workplace culture. Eric Bruce, Head of Visitor Experience at Mia, won a staff grant competition several years ago for an idea he had to study workplace cultures and apply the lessons back at the museum. The organization’s core values, listed in every job description and incorporated into performance evaluations, include “generosity, agility, emotional intelligence, positive energy, and driving results.”

Focusing on how an organization is run—I mean truly reorganizing, or at least tinkering with, its DNA— has the added potential to outlive the tenure of a single leader.

Which brings us back to vision. And superheroes.

If every person on staff owns a slice of a vision, if it is embedded in the ways we work together and treat one another, can’t we each become a sometime superhero? In fact, if everyone has a piece of it in hand, when a leader inevitably departs, the vision is still present, interwoven into patterns of thinking, working, and being.

There are museums engaged in this pursuit. At times an entire organization (the Toledo Museum of Art comes to mind), but perhaps more often departments, sometimes even a person or two, working off the radar or safely within their stated area of responsibility. The experiments of such innovators should be shared, celebrated, and dissected more. Executives must encourage and support environments where shared vision and responsibility happens with increasing frequency, and recognize the staff who take such action.

Traditional leaders will need to consciously move outside their comfort zones as they solicit and listen to advice from staff at all levels and increasingly encourage others to own and interpret the vision. In essence, the vision no longer “belongs” to just the director. In fact, that is the point.

Wow!! One of the best posts I have read on effective leadership in a long time. Thanks so much!

Reblogged this on Archaeology, Museums & Outreach and commented:

A really inspiring post on that “vision” thing . . .

Thanks so much. Glad you enjoyed the post!

Excellent article! As someone who has long been fascinated by the meta/organizational aspects of museums and the ways they affect every individual staff member and the work they do, I applaud your *vision* for more expansive, inclusive, and democratic leadership in museums!

Tracy, bravo for this smart and articulate post. I am writing a book on museum leadership and always looking for real world examples of a shared approach.

Your wonderful article couldn’t be more relevant. I recently restructured our education department and realized that I needed to do the same with our museum’s vision and values statements. As a staff, we collectively reviewed and edited the changes and revised our mission statement to better reflect who we are, what we believe, and what we do. Collaboration is essential to creating a vibrant and equitable environment where innovation and integrity reign supreme. Thank you for articulating this important message so beautifully, Tracy!