A few weeks ago I shared a post questioning whether storytelling was an appropriate or useful format for museums exhibitions. This post received a number of comments, including people suggesting that stories evoke emotions, and that emotions are important for learning.

In order to better understand how stories work, I interviewed Lane Beckes, Assistant Professor of Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience at Bradley University. Lane studies social processes at the intersection of cognition, emotion, and neurobiology. His research interests include social bonding, empathy, emotion, and prosocial behavior.

Lane, what can you tell us about how stories work?

I think there are three primary psychological concerns you want to think about when considering what you want your attendees to get out exhibits and in particular the narratives embedded in exhibits. The first is attention. When someone walks in the door of your museum you need that person to first and foremost pay attention to your presentations. The second issue is related to learning – getting information into memory. You need to pay attention to get anything in, and then you need to process it more deeply to get it into memory. And finally you are interested in critical viewing. You argued in your earlier post that you don’t want people to just whole-hog accept a biased or emotionally laden view point, but to be thoughtful about it.

So, first, attention. Stories bring us into the moment, while simultaneously taking us to another place. They make us pay attention to things in a way we wouldn’t otherwise. If I give you a narrative, one of the things that happens is you move into a frame of mind in which you are coordinating between an “on-task network,” meaning that regions of your brain are involved in processing what is in front of you, paying attention to the external world and your relationship to it, and a “default mode network” which is involved in imaginative processing. Narrative is good for getting your attention to the right place. Otherwise, people are likely to solely be in the “default mode network” seen when people let their brain wander, not paying attention to here and now.

So narrative good for helping us pay attention – that’s one of the positives of narrative.

This leads to one of the potential negatives. If you provide a narrative that has a lot of emotional content, it gets us into the “on-task network” because we start taking the perspective of people in the narrative, but simultaneously we start taking on their emotional and motivational concerns.

That can be good and bad, depending on your ultimate desires. If you want people to have an objective view, that can be bad, because you are using information to create a particular perspective.

The second thing is memory. Narrative is good for memory in a lot of ways. If I give you a lot of random words, you can try to memorize them by rote, or you can put them into a story. Take the words coffee… hippo… orange…. Putting them into a story about a coffee cup attacking a hippopotamus while he is in search of an orange, you imagine pictures in your head and construct a story. You integrate sensory modalities, and give a structure and a context for that info that makes it much easier to remember. Narrative can really enhance memory. But it does this under the structure that it is given. So the flip side is that it enhances your memory for anything that fits the narrative, but it makes your memory for anything that doesn’t fit the narrative worse.

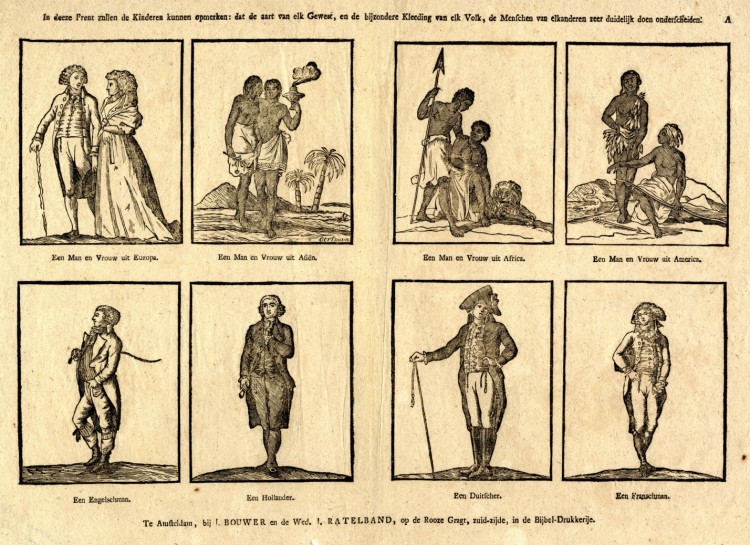

This happens all the time with stereotypes. A stereotype is like a narrative in important ways, and can be thought of as a story about how someone will act. This changes the way we see innocuous behaviors. If I stereotype someone as aggressive, and they are walking down the street quickly, I might interpret fast as aggressive.

Story determines what we will ignore, and what we will forget. If you give someone the right kind of narrative, you can get them to believe something that didn’t happen. There’s a study done by Elizabeth Loftus, that my post-doctoral advisor Jim Coan worked on as an undergraduate, called the Lost in the Mall Study. The researchers created a narrative that had a lot of true elements, and shared them with subjects. But the narrative also told the subjects about a day when they got lost in the mall – something which never happened. Six of the 24 subjects began to remember this memory as something that really happened. By creating a vivid narrative with enough true elements, people started to believe something that wasn’t true. This is called the false memory effect.

One of the things narratives do is help us construct our memories in certain ways, which effects how we think about information as it comes up. This has a powerful biasing effect. There is substantial literature showing that narrative can create bias.

Narratives can set you up to be motivated to process information in a certain way. So another possible downside of narrative is if you engage somebody emotionally you are biasing them. The fact that we tap into storytelling so easily, and take on perspectives so easily, allows us to take on other people’s motivations, which changes the way we understand something. This relates to what you were saying about stories not engaging people in thinking critically. I think your concerns about that part of narrative are probably right on.

People might be more motivated to think about material when they are in an emotional state, but they will probably be more biased because of it. Motivation and cognition are very hard to tease apart. Some people have a motivation for accuracy, which is the ideal situation for analyzing information as critically as possible, with an unbiased view. But more often people start with an emotionally motivated viewpoint. For example, two people with two different perspectives will understand a speech by Obama in two different ways depending on their political view, hopes, and desires.

If you want to increase motivation for accuracy, then you need to motivate people not to take one side of a story, but to get the whole picture. That is very hard to do.

Before we wrap up, can you revisit narrative and storytelling for a moment?

The natural inclination for storytelling is to provide a first person perspective, or at least a main protagonist and possibly an antagonist. That classical idea of story offers a protagonist as a lens through which you see a story.

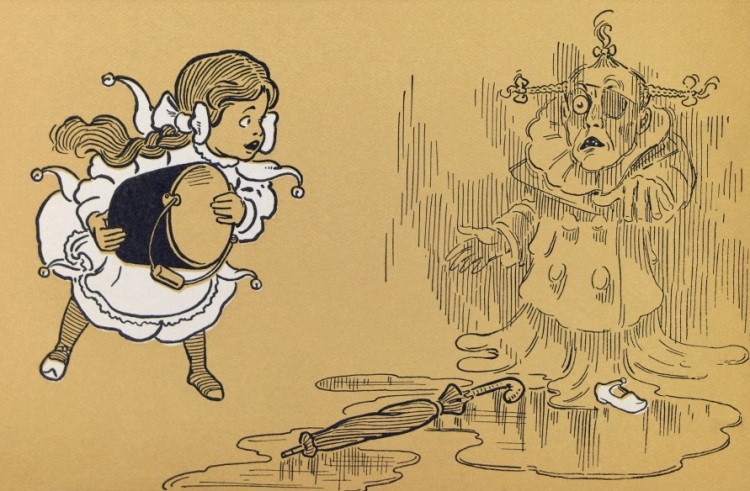

One of the things that I always think is interesting is to tell a story from multiple perspectives – to have different narrators telling a story. Multiple protagonists complicate narrative. On some level this might be a good thing – it makes people think a little more deeply about certain things. Like having people watch the Wizard of Oz and Wicked at the same time.

But I don’t know the literature of stories told from multiple perspectives. It may take away the benefits of narrative, because it makes it so much more cognitively demanding, it may be harder to get the information in memory.

Some of the responses to my previous post were about motivation, and the relationship between emotion and motivation. Can you talk about this?

In some way, all of our cognition is infused with motivation. It’s very hard to tease apart people caring about something and learning about it. You have to care to think; otherwise what’s the point? Our brains are designed to make us not think about anything we don’t think matters – they don’t want to do a lot of work if they don’t have to.

As long as you have a motivation to learn you are going to learn. Sometimes motivation is caused by an emotional response to a situation, usually because you are creating a problem to solve. That leads again to more focus, more integration of situation, more cognitive effort.

Emotion can be good in some contexts. At other times, emotion is just distracting. If the emotion is overwhelming you, the best option for you is to decouple yourself from the stimulus that is making you feel emotional – to walk away. That won’t help anybody learn. You have to be careful about how much emotion you are triggering.

Negative emotion actually tends to get people to be critical thinkers. Positive moods make people worse critical thinkers, because they become more open and accepting. Negative moods, alternatively, lead people to nitpick, negative moods promote problem solving.

Emotion has a complicated relationship to learning. Some of the fundamental elements of emotion are necessary for attention – there can be a very small amount of emotion that doesn’t really feel like emotion to the person. It’s not emotion the way we usually think about it.

Interpretation is fundamentally what we would call a cognitive task. Learning and cognition always have emotion and motivation underneath. It’s a question of how much and what kind. That’s where the complexity gets involved. Depending on the outcome you want, the type of learning you are going to get, it might be better to have a high emotional content – to steer someone into deeply experiencing something, where it’s more about seeing one perspective intently. But if you want people to analyze a few different viewpoints and think about contextual elements leading to people having different opinions, than maybe you don’t want high emotional content.

One last example: Let’s take the debate over abortion. Start with the pro-life perspective. If I’m vehemently pro-life I might be very fluent in certain narratives, and have a nuanced understanding of the issue from that viewpoint, and have none of the information that people on the other side of this debate have. I can get very deep with that particular bias. But often other perspectives are left out or contradicted. Thinking in a particular way more deeply can create an inability to think in other ways.

Another example, really the last one, scientists often get more paradigmatic as they age – they become entrenched in a way of thinking about the world. Younger people come along and ask, “why are you thinking that way?” Older and younger scientists can have a hard time communicating because the language and the assumptions the older scientists are using are so specific. Narratives are little versions of that: they create blinders at the same time as they create a deeper understanding.

Reblogged this on Jacaranda.